More McLaren

However, I like it a lot. Mark Dricoll gives a very positive review to McLaren's new book about Jesus. A good friend of mine gives a great review, too. I'll need to pick that one up eventually.

Junk and stuff and things of that nature.

Study the stand-up comedians. Stand-up comedy and preaching are the only two mediums I can think of in which someone walks onto a stage to talk for a long time to a large crowd. Dave Chapelle, Carlos Mencia, and Chris Rock are genius at capturing an audience using irony and sarcasm.

Labels: original writing

Genesis

Beginnings. The first 11 chapters are big, huge, world-wide in scope. God created the world good, but mankind messed it up. So God promises to redeem the word. He shows his anger at the rebellion of mankind by a huge flood, but miraculously saves Noah and his family. Chapters 12-50 zero in on one family. God chooses Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Jacob’s family goes to Egypt because of the provision of Jacob’s son Joseph. This book is mostly narrative literature – the story of the beginning of creation, sin, redemption, and Israel.

Exodus

Redemption. Moses is born and survives miraculously. He is banished from the Pharaoh’s presence, and God appears to him in a burning bush in the desert, saying, “Tell Pharoah, ‘Let my people go!’” God sends 10 plagues on the nation of Egypt, and finally the people are allowed to leave. They miraculously cross the Red Sea. God gives the 10 commandments. The second half of the book gives guidelines for building the tabernacle, a sort of moveable temple. This book is narrative in the beginning, but contains a great deal of construction plans toward the end.

Leviticus

Law codes. Civil laws, ceremonial laws, moral laws, case laws. This is a law book. It is named for the Levites, the keepers of the law.

Numbers

This book is named for the census taken in the beginning of the book, and the one at the end. It begins and ends with lots of numbers. Almost the entire book (the middle) is the narrative stories during the wandering of the Israelites in the Sinai desert.

Deuteronomy

A restatement of the law in the terms and forms of typical contracts of the day. “Deutero” means “second.” And “Nomy” means “law.” This is the second presentation of the law. The first is in Exodus and Leviticus. This presentation is different in format, but there is a great deal of overlap, with the law codes of Leviticus, which are much less organized.

Joshua

In two parts, the conquest of Israel, and the settlement boundaries for each Israeli family. Notable story – the walls of Jericho come down.

Judges

A series of bad leaders (that get worse) in Israel. Notable leaders are Gideon and Samson.

Ruth

Short romantic and redemptive story that happens in the time period of the Judges.

1&2 Samuel

The Rise and Fall of King Saul, and the Rise of the Davidic Dynasty. Notable stories – David and Goliath, David and Bathsheeba.

1&2 Kings

The Reign of Soloman, the split of the kingdom, the dynasties of the North and South. Assyria conquers the North, Babylon conquers the South. Notable story – Elisha and the prophets of Baal.

1&2 Chronicles

Retelling of the stories of David and Solomon from a more kingdom-oriented perspective. They are seen in a more public and glorified way. Many parallels with 2 Samuel and 1 Kings.

Ezra/Nehemiah

Originally one book. Tells the story of the return of the Jews from Babylon to Jerusalem after the exile. Notable story – Nehemiah rebuilds the wall of Jerusalem.

Esther

Short story. While in Persian exile, a Jewish lady becomes queen, and risks her life to save the rest of the Jews from genocide. This book does not mention God, but he is clearly “behind the scenes.”

Job

After a short narrative setup, this is a variety of poetical speeches looking at the problem of pain and suffering through the eyes of a man named Job (usually pronounced “Jobe”). The story has very few details and only serves to introduce the problem of pain. We don’t know when Job lived, if at all.

Psalms

This is the songbook of the Old Testament. Each chapter is the lyrics to a different song. There are a variety of different kinds of songs, written by a variety of authors, describing the full range of human emotion. King David wrote many of the psalms, and many are anonymous. They are meant to be used for corporate and private worship, they all are in relationship to God – most are in the form of a prayer. It is difficult, perhaps impossible to find a structure to the book.

Proverbs

A long list of proverbs. Very little (if any) structure. Most of the proverbs were probably written by King Solomon. These proverbs describe, in striking images, how the world usually works.

Ecclesiastes

Solomon’s meditation on the futility and meaninglessness of life on this earth. The title comes from a Greek word meaning, “Teacher.” This is how the author identifies himself in the first verse.

Song of Songs

Also known as, “Song of Solomon.” A series of very erotic and explicit love poems between two lovers. The book treats sex plainly, but not in a crass or crude way.

Matthew

Authored by one of Jesus personal friends. Written to a Jewish audience, and spends a good deal of time showing how Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament.

Mark

Written by a close associate of the Apostle Peter, the leader of the early church, and friend of Jesus. Very fast-paced gospel, has very little of Jesus’ speeches or sermons.

Luke

Written by a very careful physician as if he were an investigational reporter, for a non-Jewish audience. This is the longest of the gospels. Luke emphasizes the work of the Holy Spirit, Jesus’ teachings on money and his teachings on radical equality for women.

John

Written by Jesus’ closest friend, much later than the other gospels. John’s gospel is less like a biography and more like a sermon. Only a few incidents are recorded, but John spends a long time on each one, showing the theological and pastoral significance of each one.

1. The Nile river was turned into blood. This caused the fish to die and eliminated much of the drinking water (Ex 7:14-25).

2. The plague of frogs (Ex 8:1-15).

3. The plague of lice (Heb. kinnim, also translated “gnats” or “mosquitoes”) (Ex 8:16-19).

4. The plague of flies (also translated “dog-fly”) (Ex 8:21-24 ).

5. The murrain (Ex 9:1-7). Much of the cattle and livestock (of the Egyptians only) were killed by terrible disease.

6. The plague, of "boils and blains" (Ex 9:8-12).

7. The plague of hail, with fire and thunder (Ex 9:13-33).

8. The plague of locusts, which covered the whole face of the earth, so that the land was darkened with them (Ex 10:12-15).

9. The plague of darkness (Ex 10:21-29) covered "all the land of Egypt" to such an extent that "they saw not one another." It only occurred where the Egyptians were.

10. The plague of the death of the firstborn of man and of beast (Ex 11:4,5; 12:29,30).

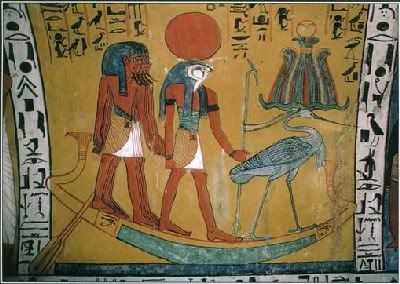

Many have attempted to give an explanation for why these plagues were chosen rather than any others. One such attempt is discussed in this paper: the plages were a polemic against the gods of Egypt.

The Position Presented

There is one clear passage giving the reason for the specific plagues, Numbers 33:4.

“. . . while the Egyptians were burying all their firstborn whom the Lord had struck down among them. The Lord had also executed judgments on their gods.”[i] This commentary on the story in question gives a different and enlightening perspective on the reason the plagues were given. In Exodus, it appears they are simply to persuade Pharaoh to let the people go (this is accomplished by sufficiently showing the supremacy of Yahweh to any other gods). However, we see more clearly the attack of Yahweh against the gods themselves as a reason for the plagues in Numbers.

There are many Egyptian gods that are well documented.[ii] Each town and city had a different (but very related) set than all the others. Some universal gods had (more or less) different traits in some cities than in others.[iii] It is therefore difficult to pinpoint what gods were attacked by what plagues. The following explanations take a generalized view of the gods they refer to.

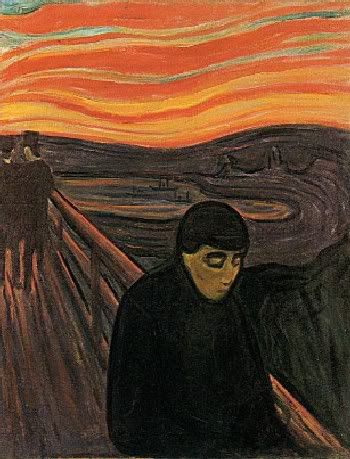

…the theology of the cross says that God comes to us through weakness and suffering, on the cross and in our own sufferings. The theology of the cross says, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The theology of glory on the other hand says that God is to be found, not in weakness but in power and strength , and therefore we should look for him in signs of health, success, and outward victory over life’s ills.[9]

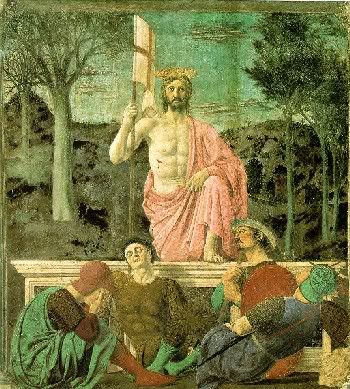

I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection from the dead.[11]

In contrast to this racist view of God, black theology proclaims God’s blackness. Those who want to know who God is and what God is doing must know who black persons are and what they are doing. . . . It is to be expected that whites will have some difficulty with the idea of “becoming black with God.” . . . “Who can whites become black?” they ask. This question always amuses me because they do not really wan tto lose their precious white identity, as if it is worth saving. … The question “How can white persons become black?” is analogous to the Philippian jailer’s question to Paul and Silas, “What must I do to be saved?” … The misunderstanding here is the failure to see that blackness or salvation (the two are synonymous) is the work of God, not a human work.

Reconciliation does not transcend color, thus making us all white. The problem of values is not that white people need to instill values in the ghetto; but white society itself needs values so that it will no longer need a ghetto. Black values did not create the ghetto; white values did. Therefore, God’s Word of reconciliation means that we can only be justified by becoming black. Reconciliation makes us all black. Through this radical change, we become identified totally with the suffering of the black masses. It is this fact that makes all white churches anti-Christian in their essence. To be Christian is to be one of those whom God has chosen. God has chosen black people!

It is to be expected that many white people will ask: “How can I, a white man, become black? My skin is white and there is nothing I can do.” Being black in America has very little to do with skin color. To be black means that your heart, your soul, your mind, and your body are where the dispossessed are. We all know that a racist structure will reject and threaten a black man in white skin as quickly as a black man in black skin. It accepts and rewards whites in black skins nearly as well as whites in white skins. Therefore, being reconciled to God does not mean that one’s skin is physically black. It essentially depends on the color of your heart, soul, and mind. Some may want to argue that persons with skins physically black will have a running start on others; but there seems to be enough evidence that though one’s skin is black, the heart may be lily white. The real questions are: Where is your identity? Where is your being? Does it lie with the oppressed blacks or with the white oppressors? Let us hope that there are enough to answer this question correctly so that America will not be compelled to acknowledge a common humanity only by seeing that blood is always one color.